So much of the truth about St. Nicholas has been hidden by the myth. You see, in Medieval times “good people” were big business. If you could get your local “goody two shoes” to be recognized by others as a saint, you could create huge money for your community through religious pilgrimages, and just like today, money meant jobs, stuff, and security. Pilgrimages were the tourism of the middle ages. A whole industry developed around exaggerating what your local saint had done, so that pilgrims came to your town and not the town next door. In this way, much of the truth about Nicholas of Myra has been lost long ago to business and trade.

As a saint, Nicholas has been a raging success. His famous generosity and the stories created to surround it soon led him to be named the patron saint of a huge number of people and situations. In fact, St. Nicholas is the patron saint of more causes than any other saint. Nicholas was such a success, the Italian town of Bari stole half his bones from his home town Myra, which is in modern day Turkey. Later, Venice stole the other half. These towns spirited his bones away to Italy, so they could become his pilgrimage sites. As more and more towns adopted him as their patron saint, his fame spread throughout the whole of Christendom, both East and West. His wide spread popularity, and the fact that his feast falls during advent, created St. Nicholas as we know him today—Santa Claus.

So after nearly 1800 years of exaggeration, business, and consumption, what do we know about the man behind the myth? Not much, but there are a few things we do know. From the beginning Nicholas was famed for his generosity. At least three early records of Nicholas’ life retell the most famous tale about him. Nicholas is said to have secretly paid the dowry of three poor women in Myra. He did so by throwing either bags of money or gold balls through the window of their home in the middle of the night. These gifts were said to have landed in stockings or shoes drying by the fire, which is why to this day we hang stockings at Christmas in hopes that we to might consume something from Nicholas. In the grand scheme of things, three sources isn’t much to go on, but when it comes to year 300 its a huge mountain of written evidence. The story is further supported as true because this act of generosity is unique. It isn’t recorded as being done by any other saint. This makes it less likely to be part of the propaganda used to lure pilgrims.

Two documents record that he was not a trained clergy person but rather was elected bishop as a lay person. Even at the time he lived, this was a highly unusual event. On a more historical note, his name appears on many early lists of those who attended the Counsel of Nicaea. In the end, it isn’t much to go on, but something about Nicholas of Myra made an impression on his home town. Within 100 years of his death, he was recognized as a saint in Myra, and that leads me to believe that at least some of the tales of his generosity are true.

So we are left with a picture of a man who lived a generous life, giving himself away to others, and placing their interests above his own. He did this as a working out of his Christian faith. Christians, like Nicholas and myself, believe that Jesus, generously gave up equality with God to become a human and love us. Because Nicholas followed King Jesus his generosity has been remembered for centuries.

But there is the rub. Here is the supreme irony of the story of St. Nicholas. We don’t take him as an example to follow. At Christmas, we don’t revere St. Nicholas as a means by which we too can learn to consume less, give more, love all, and worship fully. Rather, we place ourselves in the story as the damsels in distress. We are the poor girls who need a dowry. We have wants, we have needs, and for 1800 years we have expected St. Nicholas to meet them, and we have taught our children to expect the same thing.

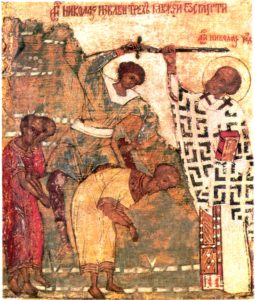

I don’t think you have to share my faith to see how much a picture like this dishonors St. Nicholas:

Nicholas of Myra must weep when he sees what he has come to represent. I wonder if he thinks it would have been better if he had never been born? I might in his position.

I think it’s time that we rehabilitate the good name of Nicholas of Myra and honor him as he deserves. If he could, I am sure that Bishop Nicholas would tell us today that the best way we can honor him is to follow his lead—to give ourselves away in loving-kindness to our neighbors as he did. That won’t be easy in a society consumed by consumption, especially at Christmas. Some sacred cows will have to die, but it’s a better story than reducing Nicholas of Myra to a pitch man for coke or a lighted plastic lawn ornament.