So I finished up the body of what turned out to be a rather long re-introduction of my blog, and I’m really not sure why I wrote it. I’m not usually one to fly the flag of my faith in my professional life. Oh I think it’s there, hanging around the edges of my science fiction. I’ve written a couple of short stories that you can find on this site that are blatantly message driven. I also don’t imagine the future as a world free of religious concerns. However, when I sit down to write a story, I have yet to write an overtly religious lead, or side character for that matter, and if I were to do so, I’d probably want to make that character a pagan or some kind of future religion before I made them a recognizable Christian.

And maybe that is exactly why I wrote this essay. If you hang around Facebook long enough you will probably guess that I am a Christian of some ilk, and when so many evangelical Christians openly support a man who brags about sexual assault—if only because he promises them Supreme Court Justices—I felt the need to make sure that my audience understands that I abhor that thinking. I want to stand up on the roof and shout “I’m not one of them. I think they’re part of the problem!”

But there’s a little more too it than that. I may believe their thinking to be wrong-headed, but if I stand on the roof of my own soul, I can see that distant country from my house. I know the road that leads there, and in a different time, I might have walked there too.

So without further mucking about, here’s a bit of my journey to no longer seeing myself as one of them. If you’re a secular person who finds yourself confused about how a Christian thinks, it might provide an interesting field guide to the inside of an evangelical Christian’s head.

A bit about my past…

I was raised in a traditional, conservative Christian household (back then we would have said fundamentalist but that word changed and evangelical replaced it). Paul (one of the writers of the Bible) says that he was a Pharisee of Pharisees, in other words, that he was the most religious among the already extra religious.

I can relate to that statement.

I come from a long line of proud evangelicals. My great-grandfather served on the board of Multnomah Bible College and helped found Central Bible Church with John G. Mitchell. (For those of you not familiar with Pacific Northwest Evangelicalism, think of John Mitchell as a regional Dwight Moody kind of character, although a couple of generations later. Still lost? He was big stuff, at least in these parts.)

When I was born, I was part of the fourth generation of Wecks’ to attend Central Bible church. The connection between the Wecks family and CB lasted for almost eighty years. I have to admit that last spring I felt an extra bit of sadness as I sat in the fellowship hall just off the sanctuary and realized that my grandmother’s memorial reception would be (for now) the very last Wecks family event at Central Bible. That church cared a lot for my family—and for me.

I attended there for the first four years of my life and as far as I can tell, I was a bit of a celebrity—at least among the Sunday school teachers. At my grandmother’s funeral, I still heard from one of them about how much she enjoyed having me pray in class. The reasons for this were varied. There was of course my name; it was a big family and well respected in the church. Then there was the bright-eyed creativity from my mother that gave me a knack for getting attention. Combine that with my full sentences at eighteen months, and I soon learned that I could get lots of kudos by praying and having the right answers.

Do you see the problem yet? No? Let’s look at it from another angle.

A bit about theology…

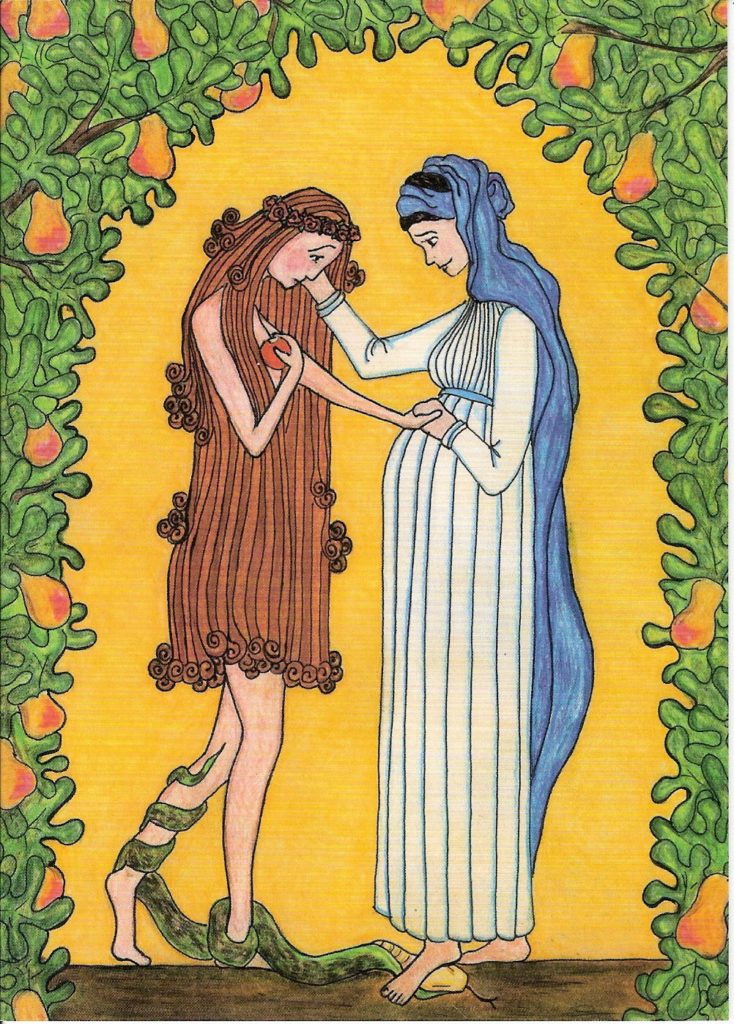

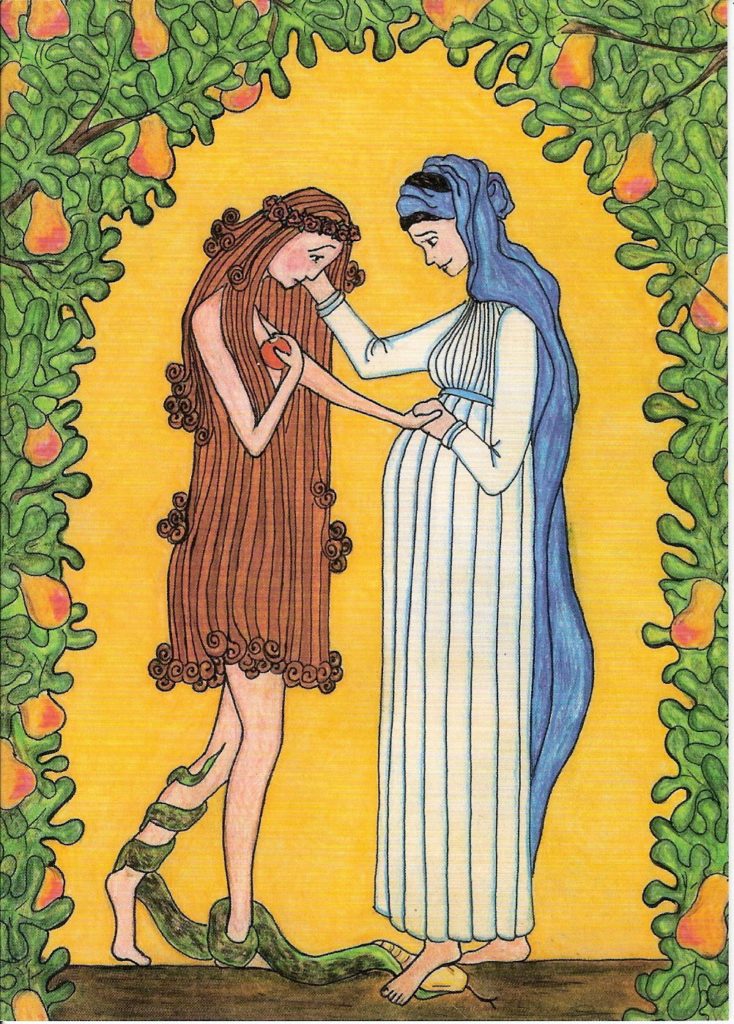

There are many forms of Christianity—even some forms that would call themselves Christian that I would not call Christian. The form of Christianity that I was raised in proposes that human beings were once in a state of perfection. They fell from that perfection through an act of rebellion, traditionally eating of a fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. This Christianity proposes that something happened at that moment that caused a rift between human beings and the creator. It is said that God is too perfect to live with our imperfection. He requires of us that we become “holy” like him before he will accept us. He has in essence turned his face away from humanity until such time as humans can be made worthy again of his presence. Without some kind of divine intervention human beings are doomed to an afterlife without a relationship with our creator—an afterlife of eternal loneliness and suffering. Jesus—and in particular his willing death on the cross—is said to be the means by which we can again become worthy of relationship with God. The blood of Jesus is said to wash away the sins of believers allowing God to once again dwell with them. Also, Jesus is thought to be God living as a human, so his willing death on our behalf proves that there is no depth to which God wouldn’t descend in order to bring us back into relationship with him. It is the proof of his love. All we need do is accept this transaction written in God’s blood as the means of our relationship with God. A fitting and proper response to receiving this love is to set out to live a similar life of self-sacrifice.

This was the theology that I was taught at Central Bible. It was the air that I breathed, the food that I ate as I was first learning to have a sense of self, and contrary to what most adults believe about kids, I understood it, and I believed it with all my heart. Even as a little child I set out to live it.

Do you see the problem yet?

Putting it all together

I don’t want to walk you through all the strang and durm that led to the eventual breakdown of my belief in this vision of Christianity. Needless to say there were a million different moments. It’s been a forty year process. One such moment was certainly reading a bit of Nietzsche in college. His question of why God would need to pay a debt that he himself created really stuck with me and made me wonder about the same question. Just cancel the debt and call it good. I never could shake that. Oh I did for seasons—talk about integrity and all—but if you think about it, it doesn’t make sense.

Eventually, I came to my own articulation of the problem. It goes something like this: the Christianity that I was raised in proposes that God holds the gun of hell to my head and says, “Love me or I’ll shoot.” By any reasonable definition, such behavior isn’t love—not even from a Creator. I think we can dress it up in a million different ways, but when you parse the message of much evangelical Christianity, it boils down to something like that. God is too perfect to be with you and unless you choose to love him he’s going to beat you with his club for all eternity. It’s your choice—love God or suffer. Oh and remember, God loves you.

I think it’s really reasonable for people outside of Christianity to wonder how this whole edifice doesn’t collapse under its own weight—and maybe that is what is happening right now. Church attendance is taking a rapid nosedive in the last few years. When Christian social scientists (Barna) went to survey who was leaving, they found out that it was people from the center not the fringes. I think lots of us are waking up from this bad dream.

It’s a bad dream made all the more difficult by its practice. The promise is that Jesus has made a way by which we can experience a sense of rightness within ourselves because we are now restored to a proper relationship with God. However, this type of Christianity proposes that our experience of this sense of enoughness is wholly dependent up on our willingness to embrace the transformation necessary to remove our basic inadequacy caused by our rebellion.

You have to perform to get the benefits—so you go to church, you pray, you read the bible, you become a “home community” leader, and you do stuff for God, like holding homophobic signs or feeding the poor depending on which you think God is asking you to do. I dare say that most Christians go their whole lives trying to live out this horrible notion that they start life as “not enough” and that they must transform their whole selves—personality, talents, desires, and everything else—in order to be acceptable with God.

For my secular friends, I hope that explains the schizophrenia of modern American Christianity. One moment they’re doing good stuff, the next they’re being hateful and trying to control what you do with your body. If you wonder how a person can stand on a street corner claiming that God is love and at the same time hold a sign that says “God Hates Fags,” look no further than this belief. If you are wondering how a Christian university president can convince himself that his student body needs to be well armed, look no further. If you’re wondering how so many evangelical Christians were willing to give a pass to a candidate who bragged about his power to sexually assault women, I honestly think it comes back to this—evangelical Christians have to be right. Their whole sense of security is based on right belief and right performance. For evangelicals, enoughness might be technically settled by the cross but the experience of enoughness is wholly conditional and dependent on our good behavior and willingness to transform ourselves.

Even as a small child, I was never enough. It didn’t matter how many times I prayed, how many kudos and gold stars I achieved in Sunday School, I never measured up. I was gifted with the ability to try—I memorized all the right verses in Awanas and led my friends to accept Jesus. Yet no matter what I did, I always felt inadequate. I was—am—ashamed of me. (I’m working on that. Thanks Brene Brown! I owe you one.)

Looking back, I have come to believe that my early church experiences both supported this sense of inadequacy and gave me the means to cope. After all, God was in the business of making me enough—making me worthy of being in his club. I developed what I like to call an annihilationist theology. I learned early on that the core me was no good. My heart was untrustworthy—”desperately wicked” as the phrase goes. It had to be completely replaced by God. He was, of course, going to replace it with someone who would want to do something important for him—like be a missionary. That sense of self carried me all the way to a year of bible college at the “family” school. Thank God it didn’t carry me into the mission field!—as it does for so many.

I believe if you look deep enough you will find in almost every Christian a deep experience of inadequacy—actually I think it’s a plague that haunts almost all humanity, but that’s a different post.

Giving Up…

I’m not sure why I never had a definitive break with my faith. There have been many times when I wished I could just stop believing and go on my merry way, but I have never been willing to make that move. Many of my writer friends have. I’m lucky to be surrounded by evangelical expats. I love those people.

I think a lot of why I stayed had to do with my family. For all its many faults, my branch of the Wecks family was a relatively loving place to be a kid. My parents too. They did the best they knew, and I think I understood that. It was at least enough for me to continue to hope that there was some way to square the wheel and find a way out of my need to perform for a God who claimed to love me but also held over my head eternal damnation and temporal blessing and used them as weapons to enforce his will. Also, I had a lot of beautiful experiences in evangelicalism, many of which I would count as encounters with the creator, so I was never really able to treat those as a mere figment. I’m still not sure why I never had a definitive break with my faith. Perhaps I still will, but I don’t think so.

For me change began when a Christian counselor friend introduced me to a book called ACT on Life not Anger. It came at a point of real exhaustion in my quest to get my life right enough for God, and I was open to new ideas. If you’re a secular person it might be readily apparent that such a theology could easily create judgmental and angry people who seek to control their own feelings of inadequacy by controlling everyone around them. Yeah… there’s me at my worst, but when you stand inside that system, it’s not at all apparent. I’m working on it.

The book was an eye opener because it proposed that struggling with feelings of anger would never make them go away, in fact it would make them worse. Instead it argued that the best way to handle your feelings of anger is to practice non-judment toward yourself and others.

So I don’t know how many of you remember Jim Rome the sports talk guy? (Yeah, I know. It was a phase.) Anyway, whenever someone would call his show and complain about referees or coaching, he would just reply, “scoreboard.” In other words all excuses aside, your team didn’t score enough points to win. I’m a big believer in the “scoreboard” theory of life. If you are wondering about whether something is good or not, just look at the scoreboard. If it’s effective, it’s good. If it’s love, it’s from God. If it’s not love, it’s not from God. It’s pretty simple like that. (Oh we can debate what is love and what is not, but that’s for a different post.)

So I bring this scoreboard theory up because as silly as it may sound to many of my secular friends, it was actually quite a revelation to me to find out that when I worked really hard to replace my judgment with compassion, it made me a better husband, father and friend. It worked. I was more the person I wanted to be when I didn’t judge. I was more loving and so to me more Godlike in my behavior.

However, this created giant cracks in my concept of God. Up until that point, my Christian practice had largely been centered around judging myself and trying to be good enough to experience God’s blessing. At the center of that practice of life sat a judgmental God who held himself separate from fallen humanity because of our rebellious and desperately wicked hearts. Yet, all the judgment I had toward myself had never helped me be a more loving person. In fact it had created the opposite effect. Now I was finding better love through giving up my judgment. So if I follow the “scoreboard” theory of life, it follows that something was desperately wrong with my intellectual concept of God. Judgement and love no longer worked for me. I needed something new.

What do I believe now?

(So thus far, I’ve only expressed the dilemma. That’s a much easier thing for more of us to agree upon. Moving forward, this gets a little more personal. It’s my attempt to make sense of life. Read it not as an attempt to convince you of anything—could I?—but rather an expression of my way of making life work within a Christian framework. To me it shows a way of thinking about Christianity that allows space for a truly non-judgmental approach to life and thus a life led by compassion rather than pride and hubris.)

It might seem like this was the moment when I would abandon Christianity all together and strike out on my own, finding God in the milieu of believism that makes up modern American spirituality, but actually the recognition that my concept of God was flawed had the opposite effect. It sent me back to try and understand anew the faith where I had experienced God despite it’s very ineffective theology and practice.

After my discovery of the effectiveness of non-judgment as a way of life, I spent a lot of time wondering about two things. First, once I started replacing judgment with compassion, it became instantly clear to me that the idea that I was somehow fundamentally flawed would no longer do. It was time to leave that nonsense behind. I was enough, worthy of love just as I am. (The same counselor who introduced ACT on Life… pointed me to Brene Brown, whose book Daring Greatly was highly influential here.) Many of my actions might violate my values and be ineffective in creating a loving planet but seeing myself as in need of annihilation was not the answer to this dilemma.

That left me wondering what exactly was God trying to communicate with the story of humanity’s fall? If we’re OK as we are in his eyes why the Garden of Eden story? Also if I wasn’t somehow in need of a magical transformation by Jesus’ precious blood, what was all that death nonsense about? Answering those two questions became essential if I was to transform the faith I had been given as a child. Without answers I felt that I would be forced to conclude that God could not be found in Christianity at all.

The answer to the first question came from a simple, careful reading of the Genesis text on the fall. As I said way back at the beginning of this essay, the Christianity I was raised in proposes that there is something so flawed with us that God must hold himself separate from us until we can be made worthy of relationship with him. However, I would propose that the Adam and Eve story says just the opposite. It is we who hold ourselves separate from God, trying by any means to prove our worthiness. After they ate the magic fruit, Adam and Eve hid, sewing fig leaves to cover their genitals. It was God who came to the garden begging them to come out of their hiding and lean on him. If death became a necessity for us after the fall, it isn’t because God cannot handle our sin, it is because we cannot consistently handle the perfect love of God without being ashamed of our imperfection. In this vision of Christianity, shame isn’t the proper response to the bitter broken state of our heart, it is the problem. Shame is the knowledge of good and evil internalized. It is the thing which keeps us going to our own resources and trying to be enough on our own instead of being vulnerable to the perfect love of God.

(For those of you playing along at home, you might hear a little bit of Rousseau in this—I see ennui as a form of shame, a sense of inadequacy. I’ve always liked the opening of On the Origins of Human Inequality as a statement of humanity’s condition, and Rousseau himself saw it as a statement of theology, dedicating the essay to the city state of Geneva, where he had been banned for heresy. I have read that he hoped that the essay would put him back in the good graces of the church there. Needless to say the calvinist theologians of Geneva were not persuaded. However, I think he provides a pretty good foundation for thinking about the psychological dilemmas most human beings enact. He seems to describe the fall quite well. The rest of human experience—maybe not so much.)

The second question, the one about the cross, was much more difficult to answer. In the evangelical notion of Christianity, Jesus blood is necessary to cleanse us because in our current state we are so dirty that a holy God cannot abide our presence. For a long time when thinking of the Cross, I felt it inevitable that I would be forced to conclude that Christianity taught that God needed blood sacrifice to get rid of his anger. Yet such thinking was so opposite to my own learning on anger. Anger only truly goes away when I willingly accept the hurt caused by another. Anger diminishes when I accept that I will never be paid back. This acceptance allows me to live in this moment and do that which is worthwhile in the present, instead of dwelling in the suffering of the future or the past. Acceptance and non-judgement allow me to be a compassionate person. As I started to live out this new thought, I kept being struck by how opposite it was to the narrative of God. God got paid by Jesus dying and shedding blood—vengeance was had by God on Jesus, and I escaped. He got to stomp his feet and demand retribution. Yet here I was so clearly learning a different and better way, that had real effects for good in my life, and I truly believe it was God himself that was teaching me this new way.

Let me start by saying that the idea of a God who is so offended by sin that he won’t dirty himself with it seems to me contrary to all evidence in the Bible. If you read the Bible you will find that God is continuously trying to interact with humanity and it is we who are continuously pushing him away—Moses at the burning bush, Israel at the Mountain of God, the whole book of judges. I could go on.

This one really hung me up for a while. If the cross wasn’t about payment to calm down an angry God what was it about? I did some reading and thinking. I found the theologian NT Wright to be particularly helpful on the topic.

In the end, I think that the simplest answer is the best. If we take seriously the notion that our human ability to self-reflect combined with an internal knowledge of good and evil create a paralyzing shame, an open relationship with a perfectly good God becomes impossible. No matter what God says, we cannot expect him to love us unconditionally nor can we be vulnerable to him. He is too good, to perfect and we are doomed to always be afraid that our next imperfection will finally be the one in which he rejects us. So instead we bargain, or we hide, or we look around and conclude he doesn’t exist. The only way to change this dilemma would be for God to prove that he will love us no matter what we do—and this to me is the magic of the Cross. It is one thing to say that I will forgive anything you do to me, it is another to show it, to perform it and make it real. Jesus—who Christians believe to be God incarnate—died to make real the truth that God will forgive us no matter what. It wasn’t just a metaphor or play acting either. In forgiving the humans who killed him while on the cross and treating them without judgment or anger, God made real something that wasn’t real up to that point. I believe there is real magic in the words, “Father forgive them for the don’t understand what they are doing.” In the history of the world there has never been a stronger magic spell than those words. They did real work, demonstrating that no matter what we do, we are enough in God’s sight. He will never reject us or judge us. All judgment was used up on the cross. In this way, I have come to believe that Jesus did open a door to God that had been closed previously, but it was not God who closed it, it was us. God never needed to be convinced to accept us warts and all. Instead it was us who needed to be convinced that he could accept us warts and all.

So where does that leave me? I still think of myself as a Christian but not an evangelical. I love God to the best of my ability and I am learning to see myself as enough, despite my real imperfections. I am trying to replace all my judgement with compassion—and I have found Buddhist thinking important here. Overall it seems a better foundation for compassionate living. It also seems to make much better sense of the Bible than evangelicalism and that for me is important.

So will anyone read this blog post? I don’t know. I guess I hope that some of you might be interested in what goes on in the noggin of someone who creates the stories that you love. But read or not, this is my way of shouting, I’m not like them! And that seems to me to be all the more necessary in the coming years. Love and compassion will win. They already did.

Thanks for sharing Erik. I hope it opens up dialogue for you with both Christians and the seekers. I thought you were able to articulate your position well. Hope you and your family are doing well. Debby and I miss the two of you.

I love you Harry Flanagan! So much of this is from you! I appreciate your influence in my life.

A thoughtful and well-reasoned post. I wish more religious folk (of all stripes) would embrace compassion and non-judgment the way you have. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Ellen! I always appreciate thoughtful conversation!

A deep insight, Erik, I feel honored to have read and understood a little piece more of the great man that you are.

Sounds like this has all been a difficult (and ongoing) journey. I wish you well on finding and holding onto that peace of self that everyone should have.